The Myopia of Professionalism

Schizophrenia is the ego-crisis of the cyborg. How could it be any other way? -- Phoebe Sengers, 1996, "Fabricated Subjects: Reification, Schizophrenia, Artificial Intelligence"

Part 1: The Invention of Managerialism

1a. Now the metrics are setting us

In 1959, C.P. Snow famously lamented1 that his fellow British intellectuals did not know how to read science. Whilst they did not value reading science, they would deride scientists for not reading more broadly. I think about this story a lot, not because the scientists were smarter and more worldly than the intellectuals, but because the intellectuals disrespected the scientists. But domain chauvinism works both ways. The scientists with their objective ways of knowing would disrespect the intellectuals and their humanities right back, and now the pendulum has swung fully the other way.

Google recently fired their ethics researchers, as we know. (My take, for what it’s worth: if Google is going to be the infrastructure responsible for indexing all the resources that people use to learn new things, be they content or courses or instructors themselves, then yes, they should actively reflect about their role in society.) This led to discussions about whether social criticism of technical systems is real scholarship. I find this whole episode points to a deep-seated communication problem in professional culture, above and beyond mere distrust of academia. This is a blog post about the structural causes of knowledge transit bottlenecks, why they've fucked up tech workplaces in particular, and a restatement of Stengers’ call to action for the HCI context.

1b. The golden goose of industrial chemistry

Isabelle Stengers' Plea for a Slow Science2 argues that the scope of knowledge for which each individual professional is responsible has been narrowed so far that each person in the workplace is utterly disempowered; they are an expert in doing the thing, but not in thinking about it, or vice versa. She makes this argument on the basis that professional knowledge is highly curated, as in the case of industrial chemistry, in order to reduce the 'time to degree' from a lifetime of learning the craft to a clearly demarcated 4-year program. An unfortunate side-effect is that professionals are discouraged from critical forms of work, and experts are discouraged from technical forms of work. Thus, when critical perspectives on genetically modified corn (to adopt Stenger's example) attempt to enter professional contexts, they are disbelieved and suppressed by other experts themselves, in collusion with vested interests.

I propose that experts supply and evaluate criticism, just as professionals supply and evaluate metrics. When you've got no metrics, you've got no product. But when you've got metrics that bar themselves against criticism, you've got Goodheart's law to tell you that the product is going to fall apart. I see this happening a lot in interdisciplinary workplace contexts, where one domain language runs up against another and we get in a fight about which one is right / more rigorous / easier to understand / etc., instead of understanding how the perspective of one captures what is missed by the other.

Part 2: Crises of Knowledge Transit in the Modern Workplace

2a. To make legible is to pass between domains and levels of abstraction

The essential difficulty faced by experts is in calibrating the boundaries of the workplace conversation. In game design terms, meetings are powerful rituals of joint attention, and it's good to explicitly negotiate what they're about. When that's too costly, it's also good to use a boundary object - a report, a map, a dataset, any of these things, - to hold space for more than one perspective in the discussion. Otherwise, I've found that it's easy for smart people to have a weekly meeting and be completely stuck at a fixed level of abstraction, able to share knowledge but not to create new understandings of a shared problem.

Gloria Mark et al. write that3 internal processes at NASA rely heavily upon a working understanding of reports, demos, and other evidence of project success in their capacity as boundary objects. Similarly, all complex workplaces need a working theory of boundary objects to engage themselves successfully within and across domains of knowledge, each containing multiple well-defined levels of abstraction.

This subject leads us toward the intricate entwining of evaluation in workplaces post-Fordism, explainability in AI, and their surprising connection through the anti-psychiatry movement; but this connection is out of scope for the current post. (I am reading this interview with Robert Chapman about his book on neuronormalcy and enjoying it greatly.)

2b. The eye distrusts the hands; the hands distrust the eye

I think about Monica Harrington's effort as a professional woman to write herself back into the history of Valve, which obviously should not be necessary, when I try to understand why my work must be visible (or else my career will not progress). I think of Snow's two cultures, wedged apart by abundance-scarcity cycles in university funding, when I try to understand how my department in engineering was 'the good one' on our campus: we were the ones who knew why graduate students in the humanities departments led a historic UAW strike, despite being every bit as precarious as us, and thus vulnerable to retaliation.

I also believe that Susan Leigh Star's theory of boundary objects serves to articulate why some collaborations across multiple disciplines are more likely to be successful than others4. Star observed that interactions at a natural history museum between administrators, professionals, and amateur birders were productively mediated by a new taxonomy of birds. As all taxonomies are imperfect, so this taxonomy was imperfect from either the scientific perspective of the professionals, or the fieldwork perspective of the amateurs. Nonetheless, it encouraged the birders to collect examples of different species which appeared similar, in preference to examples of the same species with appeared different, and this made the scientists much happier.

If you have had a communication problem due to technical complexity at work, then you have encountered the bottleneck in your knowledge transit network. Managers have experts who don't understand their concerns; experts have managers who won't listen to them; and around it goes. Perhaps there’s something wrong with all of upper management; perhaps there’s something wrong with all the non-technical people. Identifying the outgroup isn’t ultimately going to help us here. We need to make our domain languages into tools that work with other disciplinary practices, not just our own; and when that fails, we need to fill in the gaps with sketching practices, paper tools, and other multimodal practices of joint attention.

Snow, C. P. (1990). The two cultures. Leonardo, 23(2/3), 169-173.

Chapter 5 of Stengers, I. (2018). Another Science is Possible: A Manifesto for Slow Science. Germany: Polity Press. See also, transcript of the author’s invited lecture (2011).

Mark, G., Lyytinen, K., & Bergman, M. (2007). Boundary objects in design: an ecological view of design artifacts. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 8(11), 34.

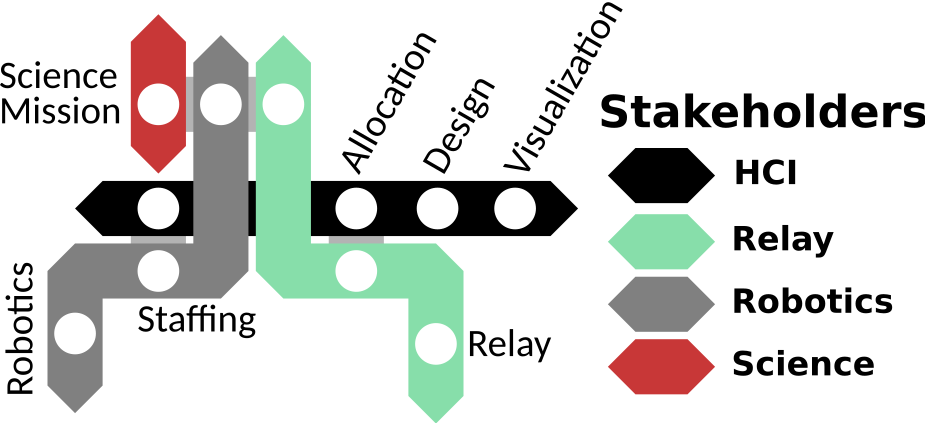

Forty-eight references on boundary objects in design studies and related forms of knowledge-intensive cooperative work are collected in my paper for the upcoming BELIV workshop at IEEE VIS.